Featured Image By: Markus Winkler on Unsplash

An open educational resource that I found impactful was Coursera. It’s an open educational platform that offers both free and paid courses from different universities and organizations. Most of the courses are free and allow for others to reuse and redistribute the material, which makes it easy for people to access quality learning materials without barriers. I find it impactful because it uses different types of multimedia and interactive materials that ensures the learners are engaged and proactive about their learning journey.

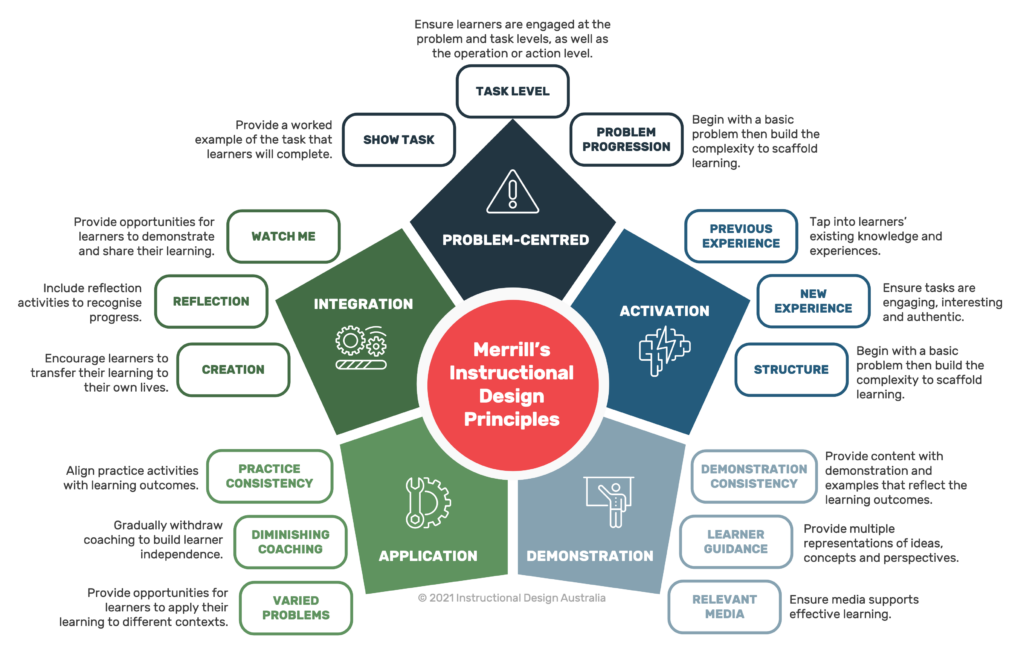

The platform starts the learners with what they know already before going into demonstrations through videos and/or real world examples. For instance, the instructors start with short review quizzes or reflection questions to recall any prior knowledge before introducing new material and then proceeding to show video demonstrations or case studies. They begin with active learning to see what the learners knows, however this may vary depending what course the learner chose. Thus learners apply what they learned through the practice exercises by discussing their new skills in forums or quizzes. As shown on Figure 1., there is a cycle of activating, then demonstrating, applying, and integrating what the learner gained throughout the course. Likewise, it also mimics the ICAP framework where deeper engagement happens when learners transition from passive learning to interactive learning (Chi & Wylie, 2014). Coursera offers feedback, forums, and group projects as part of their interactive learning. As for the accessibility, Coursera follows the UDL principles through having transcripts, captions, adjustable playback speed, and mobile accessibility for a diverse range of learners.

Overall, the platform continues to be a great resource for education for any learner wanting to delve into new material and have the same opportunity without any barriers.

References

Chi, M. T., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational psychologist, 49(4), 219-243.

Discover Learning Designs. (2021, June). How to apply Merrill’s instructional design principles. https://discoverlearning.com.au/2021/06/how-to-apply-merrills-instructional-design-principles/

Merrill, M. D. (2002). First principles of instruction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 50(3), 43-59. SpringerLink+2ERIC+2

Merrill, M. D. (2007). First principles of instruction: A synthesis. In R. A. Reiser & J. V. Dempsey (Eds.), Trends and issues in instructional design and technology (2nd ed., Vol.2, pp. 62-71). Merrill/Prentice Hall.